We left Crested Butte packed for a five day stretch that would bring us to Leadville, the highest town in the United States. Already while hiking in Colorado we met more people than in the whole states of Nevada and Utah. Though Barrett hiked with us for awhile in the same west-east direction, we encountered no long distance hikers coming the other way, on the ADT or any other trail. Indeed, we met very few hikers going either way at any distance; most of our backcountry encounters were with ATV users.

That changed our second day out when we spotted a person heading westbound who appeared to be a long distance hiker, considering his gear, gait and conditioning. I walked right up to him for a handshake and declared: “You look like a long distance hiker, the first one we have seen coming from the opposite direction. Let me shake your hand!”

Given the remote area where we met, we knew each other to be ADT hikers and sat down to chat for a spell. I discovered I already knew about Mark’s former hiking partner while planning our journey. His partner publicly declared himself to be hiking the ADT the year before us for a clean water cause. Mark’s partner had dropped out and Mark took the winter off before resuming the hike in 2011.

Unlike with Barrett, our encounter would be a once only occurrence before resuming our hikes. We stretched out our chat as long as feasible, but cold weather and an approaching storm sent us moving on in our opposite directions. Mark was not likely to encounter any other ADT distance hiker for the rest of his journey. Only a handful of people thru-hike the ADT each year and most go in the same direction as Mark, the direction in which the ADT guide was written. No one would be starting towards the end of summer from Point Reyes to go eastbound, regardless.

We were more likely than Mark to encounter another long distance hiker, but not for many months, as distance hikers usually avoid hiking throughout the winter. We could not expect to bump into anyone else like us until the next calendar year, when we would hike through an Appalachian spring. Speaking of winter, the weather had a wintry feel when we parted with Mark. As our chat with him already held us up, we shortened our day in preparation for the likely storm coming.

Whether by design or accident (I do not remember which now) we landed ourselves after only ten miles at Goodwin-Greene Cabin. The cabin is part of the Braum hut system, which is much like the AMC huts of the White Mountains in New Hampshire. When we first arrived, father and son from the state of Washington were there for the muzzle loading season, which had started after the bow season ended. We trusted muzzle loaders similarly to bow hunters, equally adept at their craft and hospitable to hikers. After eating supper they left the whole cabin to us while they camped out and scoped for game.

Inside the cabin we weathered a storm that dusted the higher elevations with snow, less than three weeks after we weathered a sandstorm in the desert. We slept on mattresses near a wood stove and took advantage of the kitchen’s butter pecan syrup for our oatmeal in the morning. We did not mind at all discovering we were a little bit sidetracked from the official ADT route.

Rather than backtrack the next morning we headed out cross country to rejoin the ADT at a high pass. Orienteering to stay true to an obscure trail below treeline frustrates me, while orienteering over wide open high country invigorates me more than any other type of hiking. How do I convey such a feeling?

Imagine your youthful desire for exploration, at least for those of us fortunate enough to grow up near natural landscapes. First you explore your neighborhood, then the woods beyond your neighborhood, then perhaps the other side of the hill beyond those woods, increasingly expanding the boundaries of your freedom and curiosity. Hiking cross country over alpine and subalpine lands extends these boundaries to their most independent, wild and beautiful limits.

The day started and ended with cross country work over high country, with a dip down in the middle to a mountain reservoir where we cooked lunch. We met only two other hikers the whole day, a couple who were former NOLS instructors. That gives you an indication of our remote location. In fact, the alleged trail to follow near the end of the day disappeared through lack of use, which explains why we headed cross country over a 13,000’ pass.

Crossing the pass placed us on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, which we would cross two more times before permanently heading east away from the mountains. The approach reminded me of another one coming from the other direction, not far away but 26 years ago. After resupplying in Leadville, while staying in the firehouse during ten degree weather, the expedition I organized to hike the Continental Divide Trail left town to cross the divide.

Recent snowstorms presented about two feet of soft snow around between us and the pass, making the trail impossible to follow. For some reason we were the only people crazy enough to be heading over the pass under these conditions, which meant we had to posthole a route up to the high altitude pass. As the leader I took on that grueling responsibility. The image of looking back occasionally at my zig-zag path with the rest of the group determinedly following, remains vivid decades later. On the one hand a very satisfying memory of cohesion and determination; on the other hand a memory that explains why we had just hiked through the Great Basin desert during the heat of summer.

That memory also recalled how Cindy could not keep up with me trudging up through the snow; nor could she keep up with me now on our cross country ascent. Cindy had the most flawless stride of anyone I had the pleasure to hike behind. Her efficiency enabled her to keep up with us taller folk effortlessly on mild terrain such as the desert, but climbing a mountain takes a good deal of lung power as well as leg power.

Twenty-six years ago we sat on our large packs and glissaded down the other side of the steep, snow-covered pass, a fun reward for our labors during the ascent. Once we reached a level area we made camp before darkness approached. That night Cindy and I kept our boots in our sleeping bags to keep them pliable during a night that dipped below zero. The next morning my boots were fine while Cindy’s were stiff, despite having the same sleeping bag model.

Twenty-six years later the descent from our 13,000’ pass was instead the worst part of the day. With still no obvious trail and no snow for glissading, we took a knee-shocking route down towards the treeline. An added challenge was guessing where, once we came upon forest, the trail might finally appear. Still, we had a satisfying day with a satisfying camp that evening … and our footgear did not freeze during the night.

When we reached Leadville I headed for the fire station, with hopes to revive the memory of the hospitality our Connecticut Continental Divide Expedition received in 1985. Times changed and they declined to host us this time around. However, on the way across town to the fire station a man out in his yard stopped us to find out what we were doing. John Nicholas offered for us to stay at his place, but at the time we declined. He then offered us twenty dollars but we declined that as well. As we headed away he ran up to us, shouting that we dropped something. In my outstretched hand he placed a twenty dollar bill and ran back before I could say anything. We obviously had a place to stay when the fire station fell through.

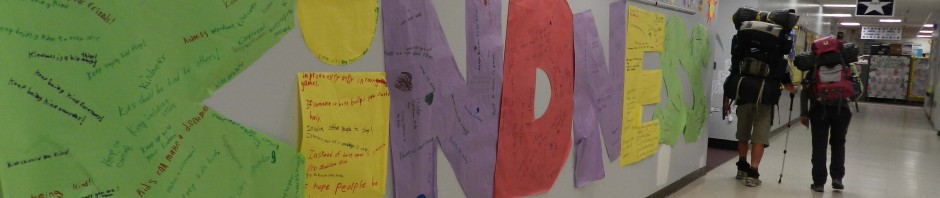

While in Leadville I presented to my second college gig at Colorado Mountain College but, as was often the case during our journey, I received more information than I gave about kindness and community. We also attended the vibrant community meals luncheon hosted at the St. George Episcopal Church. I interviewed the director to discover why this program worked so well. Ali Lufkin shared with us the three ingredients, plus the most memorable quote of our journey.

The community meals program worked to get people from all demographics attending the luncheons. The mayor attended regularly; college faculty attended, as did students. They also worked to get people from all demographics involved in the preparation of the meals, those well off and those downtrodden. Finally, they required those preparing the meals to join those coming to eat the meals. She summed up their philosophy with this quotable gem:

“We try to confuse who is giving and who is receiving.”

I see that now as the difference between community involvement, which has been waning in our country, and volunteerism, which has grown in response to the shrinking middle class and growing problems of poverty. With volunteerism people are doing things for others; community involvement tackles similar goals by doing things with others.

As we continued across the country I inserted this quote into all my talks. Colorado continued to feed one of our reasons for walking across the country with glowing examples of kindness and community. I just hoped that when winter arrived our most important reason would not be undermined by the cold we had yet to face, which would affect Cindy more.