While combing through potential scrapbook material I came upon several of Cindy’s journals. One was a journal of inspirational sayings which will be instrumental in planning her memorial service. She also kept a journal of our Continental Divide hike in 1985, a nice find because I did not keep one. At night I often read passages from that journal to Cindy, reliving the memories, playing out a nonfiction version of The Notebook.

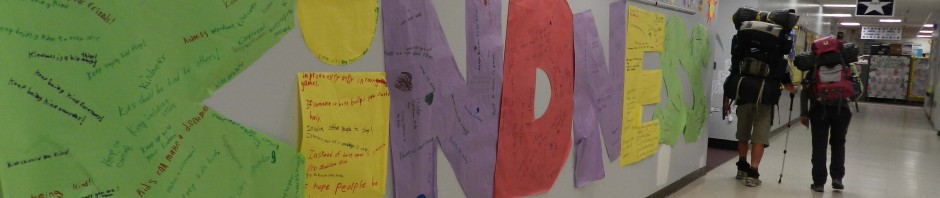

Yet the journal that stuck out the most to me was one Cindy kept for the second half of our fairly recent American Discovery Trail hike. I did not find the one for the first half of our journey but, then again, I practically wrote the entries for her. At the end of the day, for around the first three months of that year long hike, Cindy would ask me to recap what happened for her to record in her journal.

As I looked through her journal for the second half of that hike I gradually realized that I had been unaware of this journal because Cindy logged the entries completely on her own. I have cited other ways in which that long distance hike improved Cindy’s brain health; this journal was additional proof. A few months into that long distance hike she no longer needed me to remember the day’s events; she could remember them on her own.

I wish I knew back then what I know now. I wish I knew then that she had dementia, despite denials from doctors because she was too young, rather than assume at the time that she must have some type of anxiety disorder. I wish I knew then all the quality of life factors that slow down and even reverse cognitive decline, rather than think that simply removing Cindy’s stress, though very important, was the one factor that improved her brain health. I wish I knew then all the other ways besides reducing stress for which long distance hiking improves brain health through the quality of life lived. Had I know all that we may never have ended the journey.

Lately I came across an article listing six ways in which walking is good for brain health, which I posted to my Facebook page. Most of the ways point to how the chemistry of the brain is affected and expressed. Consider that cardiovascular fitness also enhances brain health, by improving blood flow and metabolism. Walking provides a small measure of cardiovascular fitness, but not nearly as much as trail running … or hiking. Hiking over challenging terrain combines the brain health benefits of walking plus the benefits of good cardiovascular fitness.

There are other proven health benefits to hiking as well, such as the benefit from sunshine. Like I said, I wish I understood all this six years ago. As I witnessed Cindy’s cognitive function improve I may have better understood a new, revolutionary “treatment” for dementia, otherwise undiscovered as those looking for drugs to curb amyloid plaques continue to fail. Alas, our “treatment” did not go far enough. Then again, in a civilized world who realistically can maintain a “treatment” such as long distance hiking? Some day I may put that to the test.

I write this as pedicab season has ended up here in the “Icebox of Connecticut,” coldest town in the state. I know for a fact the cardiovascular fitness provided me by that activity curbed the headaches I otherwise would have had from stress and microbleeding as Cindy’s decline accelerated. I still get a few.

That is why, with much determination, I have instituted a new exercise regime for those days when I have no coverage (which is most days) and cannot get out. I run up and down one flight of stairs, seven steps of about 8 inches each, 100+ times. Then I do half as many continuous sit-ups and elevated push-ups (pushing up from a counter rather than the floor, a concession for being old).

During this routine Cindy sits on the couch where she can either glance at the television set or at the nut running up and down the stairs. I can tell that most of the time she’s watching the nut with a puzzled look, not the puzzled look of one addled with dementia so much as the same puzzled look she’s given me for 30+ years, the “I married you?!?!” look. At least she takes full responsibility for the choices she’s made.

I will work my way up to 200 stairs, 100 sit-ups and 100 push-ups, a routine I can complete in about 30 minutes, the length of one sitcom. Never before would I have considered such a tedious shut-in approach to cardiovascular fitness, a Denise Austin video seems exciting in comparison, but “desperate times calls for desperate measures.” I didn’t want to lose my fitness from pedicab season; now the early returns suggest I’ve made further gains. Recently I ran up Lovers Lane, daydreaming my way up the first two hills before realizing that I was not at all out of breath.

I now figure the best exercise I could get in my constrained situation, when I can get out, would be to walk up to the top of Haystack Mountain and then do stair reps up and down the tower, adding together the brain health benefits of both walking and cardiovascular fitness over the course of the outing.

Sound a little nutty? Perhaps. That never stopped me before. Sound a little over the top? Perhaps. But then I think about Cindy’s journal for the second half of our American Discovery Trail journey, a journal she could not keep on her own for the first half. I think about dementia and microbleeding and headaches and then I conclude that nothing can be over the top that has as much demonstrated and proven benefits for brain health, moreso than any drug or other treatment being researched.

Then I think that no one should be concerned about what sounds nutty or over the top when it comes to maintaining your brain health, which leads me to share these experiences and thoughts with you. Go for a walk each day. Do some strenuous exercise that gets you out of breath for at least a few minutes each day (consult a doctor if this would be new for you). Then go hiking on challenging terrain that will accomplish both. Your brain will reward you.