We discovered Aintee’s Barbecue in East St. Louis, during our walk across the country. We had just crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois on a clear day late in December, the kind of day that allows odors to travel far. An open air barbecue attracts hikers like moths to a flame.

Here is the original Aintee’s Barbecue post from the journey.

During our journey I constantly was on the lookout for inspiring stories, Aintee’s (her real name is Lisa) was particularly heartwarming. Aintee’s Barbecue consisted of grills lying on top of 55 gallon drums cut in half, set up by the side of a convenience store. Her smile was as bright as the day as she shared with us the unique arrangement that enabled her to run her humble business.

Lisa, a black woman, became a self-appointed caregiver for James, a white homeless vet. He had been sleeping under a nearby bridge and occasionally mugged until Lisa was moved to intervene. She outfitted her truck so that James could sleep in it. During the day, while Lisa grills and serves ribs to her customers, James picks up trash around the convenience store lot. The appreciative convenience store owner, a Pakistani, allows Lisa to run her business by the side of his building. Bartering outside the grid with racial harmony at its finest!

The recent events sparked by the George Floyd tragedy got me thinking about this lesson in cooperation and compassion between races. This was coupled with another lesson from our experiences in East St. Louis. I chuckle to think at what my father’s reaction would be, had he still been alive.

As a teenager in the late sixties I witnessed the frequent spectacle of my father swearing at the television every time there was coverage of a riot. The target of his wrath were the rioters. Yet as an impressionable and observant lad I noticed my father had only good things to say about every single black person that lived in town. Every … Single … One.

True, there were very few blacks in our lily white, rural New England town, but whites did not have a similarly perfect record in my father’s estimation of character. This contrast between anonymous stereotypes and local reality left an enduring impression on me. You realize no demographic consists of wholly bad people once you get to know their individuals.

The American Discovery Trail brought us through a few cities. We hiked through dicey neighborhoods in Oakland, Grand Junction, Evansville and DC. The city with the worst reputation was East St. Louis. A mugging of an ADT hiker, widely known to the hiking community, once occurred there at night.

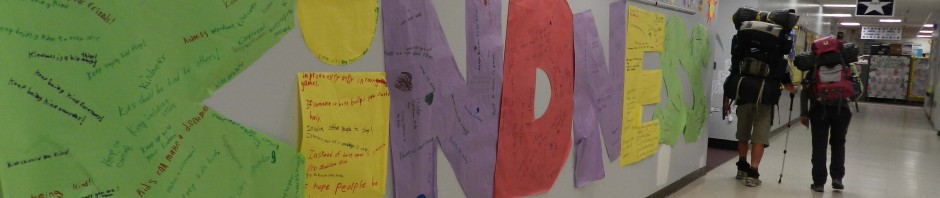

We feared no mugging as we hiked through East St. Louis. We sensibly hiked during the day and at a time of relative calm. One of my slogans in talks across the country was: “Expect trouble, find trouble. Expect kindness, find kindness.” Expecting kindness, that is what we found in East St. Louis, courtesy of Aintee’s Barbecue.

Later on in the day we had an encounter with the police. By this time we were hiking on a state road through an industrial neighborhood, Monsanto Avenue to be precise. As a person that took over 10,000 photos documenting our journey, the good and the bad, I took a picture of the factories around us. Within two minutes a squad car pulled up and two policemen rushed out towards us.

The policemen demanded I delete the photo I just took and looked over my shoulder to make sure I followed their instructions. “Homeland Security” was the reason they offered, even though any motorist could have taken the same picture without getting caught. Regardless of the absurdity of the demand, at no time did I feel threatened by the police.

This now sticks in my mind during this turbulent time: I never felt threatened in a depressed neighborhood. This also was true for every other depressed neighborhood we encountered: Oakland, Grand Junction, Evansville, DC and others. Furthermore, I never felt threatened by the police even in a depressed neighborhood where the color of my skin suggested I did not belong.

I understand this would not be true for many whites. Many would feel threatened in a depressed neighborhood of a different color. Some may have justification due to a traumatic experience in the past. Many may have fathers who swore at the television without providing the balanced perspective of local reality. All of us are bombarded with messages to encourage fear and anger, which requires great determination to resist.

Fear and anger aborts our empathy. We cannot imagine ourselves in someone else’s condition because we are too absorbed with our own, even when the threat amounts to no more than images on a television screen. Biological/hormonal evidence supports this claim, but I bet you know it to be true from experience. The more fear and anger we have, the less we empathize. A society full of fear and anger is one lacking in empathy.

For my part, my heart aches when I imagine the apprehension any black would feel if a police cruiser suddenly appears and two white officers rush out. Indeed, their apprehension extends to being in a neighborhood of a different color. Personally, I would find life to be a great burden if I was saddled with such pervasive, yet justified, apprehension. My whole life has been a counterpoint to living that way. I bet many whites with a more apprehensive lifestyle than myself would feel the same, if they applied the empathy to understand going through life with constant apprehensions.

I have a tonic for when my heart aches over such thoughts. Instead of images on a television screen, or sound bites from talk show hosts fueling fear and anger, I see images from expecting kindness and finding it all across America. Images such as Lisa of Aintee’s Barbecue, with her big heart and big, bright smile.